Exploring The World of Independent Authors: Michael Hogan

Introduction

Contrary to my usual method of meeting fascinating authors, I encountered Michael Hogan in a Facebook Group called Mexico Writers. This group is composed of Mexican writers and those who live in or write about Mexico. During the first two years of our world travels, my brother and I lived in Yucatán and wrote much about the culture.

I was immediately fascinated by Dr. Hogan’s work.

Including him in my Independent Authors collective is a stretch, for he is more mainstream than that. However, he has become a valued friend and mentor, and I could never omit him from such inclusion.

Our friendship continues to grow.

Interview

Q.1. Would you mind offering a brief synopsis of your early life—specifically addressing what led to your passion for writing?

Born in Newport, Rhode Island, in 1943, I grew up in a small-town environment, playing in the woods in summer and ice skating in winter. I loved solitary walks as a child. I loved reading, hiking, and camping in the woods. I attended Catholic school and was a bit of a juvenile delinquent in my teen years, but I got good grades and went to college on a scholarship. I was initially a philosophy major in college and very interested in jurisprudence. I got a law degree and, for some years, worked with a law firm. But I was always more interested in narrative and the shapes of language than in the law itself. So, I wrote a great deal in my journal during my free time: poetry, stories, essays. In 1975, I had a book of poetry published by a well-known press; then the following year, I received the NEA Creative Writing Fellowship. I took a year off to write. During that year, Richard Shelton, the head of the Creative Writing Program at the University of Arizona, offered me a teaching fellowship, which I accepted and received the MFA. I had many early successes for the next decade or so with my early work in poetry, short stories, and essays appearing in well-known magazines such as American Poetry Review, Harvard Review, Paris Review, and the Pushcart Prize selections.

Q.2. You are a member of the Facebook Group – Mexico Writers. When did you take up residence in Mexico, and how did that come about?

I worked as a Poet in Schools in Arizona and Colorado and for the Western States Arts Foundation. I also taught Freshman Composition and Poetry Seminar at the University of Arizona. However, I found this not very challenging, so I accepted a post in San Francisco teaching at-risk students and publishing a student magazine at several inner-city schools. As a result of this work, I was offered a position at the American School Foundation in Mexico to head their English Department and set up the Advanced Placement Program. I also founded their first student magazine, Sin Fronteras, which has since received over 30 annual awards from the National Council of Teachers of English.

Q.3. How did you come to write about history and become a professor of international relations at the Autonomous University of Guadalajara?

In our second year in Mexico, my son died. It was unexpected and shattering. I was about to quit the job since I was often on the verge of tears and depressed. But the principal, Soledad Avalos, hugged me warmly and told me, “You’re a good teacher, Michael, but you could be a great teacher if you could see your son in every child you teach. These students would come to love you.” That was a turning point; her warmth and sincerity convinced me. I agreed to stay. My two-year contract was extended indefinitely. As the months passed, however, the loss of my son continued to haunt me in quiet moments of reflection until one day, I attended a service for another child who died too young. The priest said, “When a young person dies, we often ask, ‘Por que?’ ‘Why?’ But perhaps the better question is, ‘Para que? ‘What can we do with this death? How can we create meaning from this loss?’”

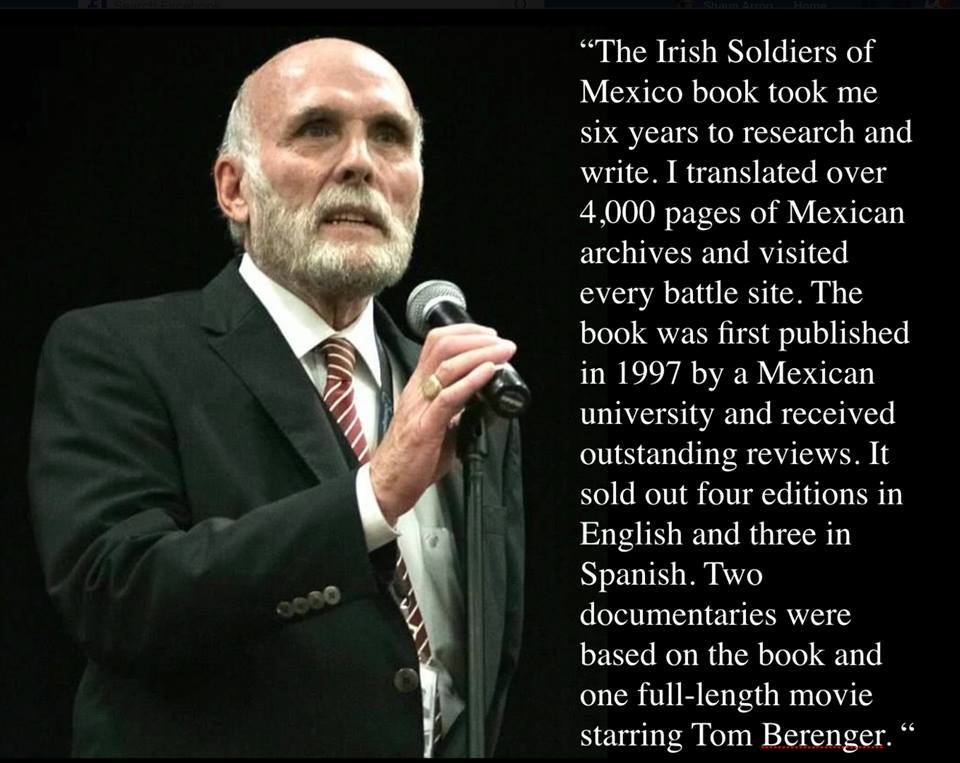

Well, my son’s dream was to become a historian. It was a dream never to be realized. So, I could give his life meaning by fulfilling his dream and doing the work he intended to do. So, I enrolled in a graduate program in Mexico and earned a PhD in Latin American History and International Relations. My dissertation was The Irish Soldiers of Mexico, a history of the Irish battalion that fought in the Mexican-American War. It was eventually published as a book, sold over 70,000 copies, and was the basis for an MGM feature film and three documentaries. It also led to my second teaching post as professor of International Relations at the Autonomous University of Guadalajara and the completion of my trilogy of books on Mexico’s history with the following two volumes: Abraham Lincoln and Mexico: A History of Courage, Intrigue and Unlikely Friendships, and Guns, Grit, and Glory: How the US and Mexico Came Together to Defeat the Last Empire in the Americas.

Q.4. Although your writing emphasizes history, you are prolific (31 books) in various genres, including literary fiction and poetry. What drives your interest in each?

As I mentioned, my first love was poetry and the narrative. Also, I was fortunate to be writing during the Seventies and early Eighties when small press publications flourished, and the National Endowment for the Arts subsidized many quality magazines. Also, there were many reading opportunities, and I was fortunate enough to not only partake in some of these but also to work with, interview, and sometimes share the stage with some of the best or at least the most exciting poets of the day. Seamus Heaney, W.S. Merwin, Marge Piercy, and William Stafford are among the former. Among the latter are Allen Ginsberg, Joseph Brodsky, and Charles Bukowski.

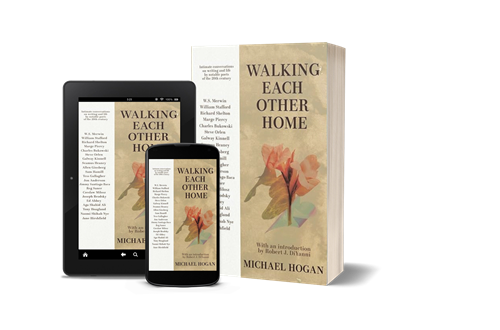

Q.5. I just purchased your newest book, Walking Each Other Home, which draws on personal encounters with some rather famous authors, including Charles Bukowski and Ray Bradbury (a personal hero of mine). Can you talk about some of these encounters and what they meant to you at the time?

Although he was rather famous when I finally worked with Bradbury, our relationship harkens to earlier. He primarily wrote linked short stories with no actual plot in Something Wicked This Way Comes and Dandelion Wine. Then comes Bukowski with his autobiographical stories, Hunter Thompson with his opinionated and participatory journalism, me with the prose poems of Lion at A Cocktail Party, and O’Brien with The Things They Carry—lots of genre-crossing and blending. Fortunately, there were publications then, Weird Tales, Stories from Beyond for Bradbury, Black Sparrow Press for Bukowski, Gallimaufry, and Unicorn Press for me. Later, some went mainstream. Bradbury’s fantasy book The Martian Chronicles was hailed as “science fiction” and became a hit among youngsters. Bukowski was published by a major press in Germany that praised his “dark existential humor,” I received an NEA Fellowship, a Pushcart Prize, and a teaching gig after the publication of my book of prose poems. O’Brien received placement in Best American Short Stories and Best American Essays for “The Things They Carried.” The press gave new names to our genres. My prose poems became “flash fiction,” O’Brien’s work became known as “creative non-fiction,” and so on.

Bukowski and I met several times in the Seventies and early Eighties. We read together on the back of a flatbed truck in the late Seventies in Commerce City, Colorado, with the Devil’s Disciples motorcycle club lighting the stage with bike headlights. We were both into heavy drinking in those days. He was not well-known as a poet, but although he broke most of the academic rules, I enjoyed his work and found him to be philosophical and deadly accurate in his assessment of the human condition.

Ray Bradbury and I finally worked together at the Santa Barbara’s Writers Conference much later when he was in his eighties. I was perhaps better known as a historian, and he was a science fiction writer. The irony is that he did not consider his writing science fiction. He said he simply wrote a human story set in the future, much like your I, Robot Soldier, or Fahrenheit 452. I was still writing narratives, but this time not imaginative, but carefully researched and documented, and I became better known as a popular historian. An MGM movie starring Tom Berenger reinforced that view.

Q.6. In your mind, which of your books most entirely and effectively reflects your philosophy of writing and your standards for the written word and best tells the story that consumes you most?

My last two books, The Michael Hogan Reader and Walking Each Other Home: Intimate Conversations on Writing and Life with Notable Poets of the 20th Century, encapsulate my philosophy and provide a selection of my best writing. The latter, as you know, is mostly about my mentors and friends with whom I often shared the stage, conferred with, or, as you and I do these days, read each other’s work, wrote reviews, and tried to convey by word of mouth our mutual respect for the work.

To sum up, I would say that these are the essential things I have learned and applied in my life and work. 1. Most writers tend to fail, not from lack of talent, but lack of character. So, I try to come to my desk daily with a plan and stick to that. I show up on time for performances and stay disciplined. 2. I realize I stand on the shoulders of those who have gone before me, so I honor my mentors and publicly acknowledge them 3. I admit my weaknesses and ask for help. I am not a good proofreader or self-editor, so I get a professional to help with both. 4. I believe in the “gift economy.” I try to help young people setting out, promote my contemporaries’ work, write reviews, and share thoughts and promotional ideas. When I receive help, I always pay it forward. 5. Inspiration is rare, but it is more likely to come when I am working, so I practice my skills and plod along on dark days and am always delighted and grateful when inspiration comes. 6. as Ray Carver once wrote, I realize that any “success” that comes along is “gravy.” The real reward is living three lives: the day-to-day life with its ups and downs, victories and setbacks, the imaginative life with its endless possibilities (which I get to create), and the reading life in which I can access two thousand years of other voices, other mentors, and other cultures that are alive in the books I read, the histories and primary sources I study, and my reflections on them. The writing life is, in every sense, a blessing and a source of gratitude. I never have a day when I am bored or left with nothing to do. Life is full of endless possibilities.

Discover more from Joel R. Dennstedt

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Magdalena Contreras

As a professor, Dr. Hogan is the best mixture of friend, mentor and guide. Students appreciate him and continue keeping in touch with him, even when they leave school.

I had the privilege of working near him and I will always be thankful for all he meant to me.

Joel R. Dennstedt

Your comments are much appreciated and easy to believe. It is my personal belief that teachers such as you describe are the MOST important people in this world. I had such a teacher in 5th grade. She turned my life around and I continued to visit her throughout my life.

Magdalena Contreras

I totally agree with you. Teachers touch lives forever .