Exploring The World Of Independent Authors: Tom Hoffman

Introduction

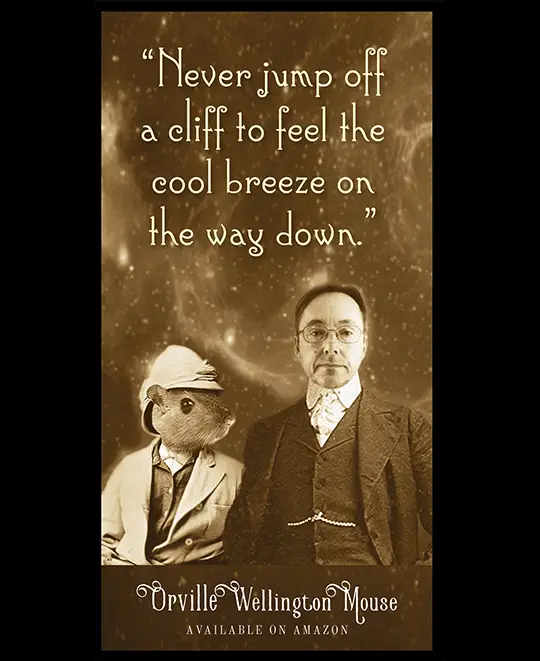

For several years, I was a top reviewer for Readers’ Favorite, a highly regarded online review site. One day, I selected an enticing little book called Orville Mouse and the Puzzle of the Clockwork Glowbirds for review. This was my introduction to Tom Hoffman and his wickedly delightful imagination. I was hooked, and my review conveyed that. Surprisingly and synchronistically, Tom replied to my review with a generous appraisal of my writing. He also offered to rework my existing book covers as they were commercially unappealing. The result can be inferred from the last line of the movie Casablanca.

Our friendship blossomed. I have read almost every book by Tom Hoffman. He writes for the young and the young at heart, and I am a devoted fan. I probably encountered Tom decades earlier when I was an office supply salesman in Alaska. His advertising company was my client. The universe works in mysterious ways. That notion provides the most direct entry into Tom Hoffman’s writings.

Interview

Q.1. It’s no secret to those who know you that your motivation and inspiration for characters comes mainly from your grandchildren. Could you expound a little on their original influence? Did they cause you to start writing novels in your sixties? How does their influence continue to inform your efforts as you age together?

Oliver Wendell Holmes once said, “For the simplicity on this side of complexity, I wouldn’t give you a fig. But for the simplicity on the other side of complexity, for that I would give you anything I have.”

My characters often say, “Bad things are usually good things in disguise.” I shall begin with such an event on this side of complexity.

When I was seven, my younger brother died of leukemia. At seven, I had no idea of the lifelong ramifications of such a traumatic event. My terrifying, recurring nightmare involved an amorphous dark creature roiling in the basement. This lasted until I turned 18. My unconscious knew what was up because that’s where the creature lived, and that creature was death. In the dream, I had to run past it up the stairs, open the door, and make my escape. Finally, I did. That early trauma ignited my lifelong quest to understand the nature of existence. Who are we? What is this place? What are we doing here? What happens when we die? All the big questions.

Along came Raymond Moody’s book Life after Life, a degree in psychology from Georgetown University, meditation, 10,000 more books, dream analysis, lucid dreaming, synchronistic events, countless paranormal events, precognitive and retrocognitive visions, out-of-body experiences, ghosts, and on and on during a lifetime of searching. I was driven to find the answers. All such transitions are chaotic and scary, but I knew that psychic phenomena comprised a room you pass through on the way to somewhere else. Don’t get trapped in that room. Move on.

At some point, I crossed over from the “simplicity on this side of complexity” to the “simplicity on the other side of complexity.” Life became staggeringly complex, but also monumentally simple. No need for books anymore, no need for paranormal events, no need for proof of anything. I was the answer. I compare it to the difference between a fish swimming in the ocean and a book describing a fish swimming in the ocean. We are it. There’s no need to read about it. I will add that life has many more dreamlike qualities than most people think. (I’m raising my eyebrows, giving you a very significant look.)

When the grandkids came along I thought, Dang, what happens if I croak before I can tell them all this stuff? I should write it down. In a fun way, easy to understand, stories with characters named after them. Cool stuff in it, like aliens and ghosts and mysterious guys with white beards who have awesome mystical powers. I called it metaphysics in a crunchy candy shell. I thought they could help me write it.

“What’s the scariest insect you can think of?”

“CENTIPEDES!”

That birthed the giant carnivorous centipedes Orville Mouse encounters on Periculum. This went on for 18 books. As they grew older, the books grew older, too. The characters faced more complex trials and obstacles. The latest series is The Ghost Ring, dealing with death, loss, grief, and tragedy but still in a funny way. It’s not too scary; it’s just scary enough.

They’ve read my books and love them. They’re old enough that I can talk about deeper aspects of the books. I can explain synchronicity and tell them about some paranormal events I’ve experienced. In a hilarious way, of course. We laugh our brains out. I should add that writing a book usually helps the author more than the reader. It forces me to distill some very complex concepts into something kids can understand. This helps me to reach the “simplicity on the other side of complexity.”

Tom Hoffman and Granddaughter

Q.2. Your characters are always endearing and consistently engaged in humorous banter between themselves. A consistent trait concerns the male character who is reluctant to assert himself, then proves to be brave beyond measure. He is often paired with a female character who is smarter but totally compassionate and supportive. Do these traits reveal more about your grandchildren or yourself?

Novels are always projections of the author’s life experience. I often say, “I am a kite, and my wife is holding the string.” We’re both retired now, but she was a registered nurse and then a CPA. She’s one of the smartest people I know, and she keeps me grounded, as do my kids and grandkids. We met in college. I once told her, “Me writing thrilling adventure stories is like an old spinster writing steamy romance novels.” I am not an adventurous person. Most of my adventures are in my head. It’s a lot safer there. I used to get lost a lot before GPS. I can visualize anything but can’t create maps in my mind. I googled it; it’s a thing — a syndrome. Some people get lost in their own houses because they can’t create maps in their heads. My wife, a retired RN, stared at me when I told her that. “You don’t have a syndrome. Knock it off. Pay attention to where you’re going, don’t start thinking about other stuff, no daydreaming.” So there you have it: Bartholomew and Clara, Orville and Sophia, Max and Grace, Odo and Sephie, Simon and Clara, Tom and Alexis.

Clara and Simon from The Ghost Ring Series

Q.3. We cannot discuss your writing without mentioning the inevitable inclusion of metaphysical wisdom. You are a master at translating ineffable truths and wisdom into nuggets for the young. Have your younger readers taken due notice of this and responded to it? Have they found it helpful in their daily lives? Have they offered any actual experiences that might illuminate these nuggets?

I covered a lot of this while answering the first question. We can never fully know our actions’ impact on the world. I write a novel, manage to stuff it in a bottle, cork it, and hurl the bottle into stormy seas. Then I go home and let synchronicity take over. I sometimes say, “My books are not for everyone, but they are for someone.” I let the universe figure out who those “someones” are. I have gotten letters from kids saying they like the books, though on what level, I don’t really know. Maybe they’ll read them again in fifty years and see something they didn’t see before … or not.

Q.4. You are a very visually oriented person. Your sense of graphic design is highly developed. I know you create all your own book covers (as well as mine), and you like to toy with AI image production. Many authors first create images in their minds and then translate them into writing. Some, like me, often start with a graphic image and create a story based on that. Where does that leave you, exactly?

My initial story ideas can come from anywhere. In Orville Mouse and the Puzzle of the Capricious Shadows, Orville sees a hat fly past him on a blustery day, the hat getting stuck in the top of a tree. He retrieves it and decides he likes it, starts wearing it. He tosses the hat onto the grass and notices that the shadow is going in the wrong direction. How can that be? This capricious shadow takes him on a quest to find the answer. This idea came to me while sitting with my wife in a Taos, New Mexico restaurant. A big painting on the wall next to us depicted a small southwestern town. The problem was that every object in the painting had its shadow going in a different direction. I recalled an art school instructor shouting, “LIGHT SOURCE, LIGHT SOURCE!” That painting became the inspiration for the book.

Most of my plots, however, come from ideas I want to introduce to the reader. Once I start writing the first draft, I see everything clearly. I visualize it in my head, then try to describe what I see. I also hear the characters talking. I laugh when they’re funny. I include colors a lot in my descriptions: a pale green door, a red hat, or a translucent blue figure. It’s what I see, and it helps the readers visualize it. Some say, “It’s like I’m watching a movie.” That’s what I aim for. I consider myself a storyteller more than a writer. I have an extremely creative imagination and am good at finding connections between seemingly unconnected things. This is great for adventure stories.

Q.5. In your mind, which of your books most entirely and effectively reflects your philosophy of writing and your standards for the written word and best tells the story that consumes you most?

They say every author’s first book is a thinly veiled autobiography. My first series, the Bartholomew the Adventurer books, probably delves deepest into the metaphysical world in dealing with the complex process of enlightenment. The Bartholomew trilogy includes the super fun idea of manifesting one’s thoughts into physical reality. What are thoughts? What are physical objects? Do physical objects objectively exist? Are they only a subjective experience?

Discover more from Joel R. Dennstedt

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.